Lieutenant-Colonel Derek Lang

5th Battalion, Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders

I can well understand why long-term prisoners feel reluctant to face the world again when finally they come to the end of their sentences and are released. Although I had fretted during the long weeks when we had been confined, now that the moment had come for action I shrank from it with something very like fear. Suddenly the big, square house seemed terribly safe, comfortable and infinitely desirable. Outside was the unknown, perilous and menacing.

(Derek Lang, Return to St Valéry, 110)

Born on 7 October 1913 in Guildford, Surrey, England, Derek Boileau Lang took a commission with Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders in 1933 after attending Wellington College, Berkshire and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He served with the 2nd Battalion in the Middle East in the 1930s and was adjutant for the 4th Battalion at the outbreak of the Second World War. He was wounded and taken prisoner during the Battle of France in June 1940 but managed a remarkable escape across multiple countries and eventually rejoined the army.

On 12 June 1940, the 51st Division surrendered German forces in St. Valery, and Captain Lang became one of 10,000 British prisoners of war. “The first moments of captivity were agonizing,” he recounted. “The loud guttural voices of our captors, their swagger and arrogance and perhaps above all their smart turn-out, which compared so noticeably with our own pitiful appearance, increased our natural despair.” He was sent to hospital under guard due to a shell wound and then forced on a prisoners’ march toward Germany. After several days, he broke ranks with two other officers Johnnie Buckingham and Fred Corfield: “I cannot adequately describe our feelings in those first few hours of freedom. There was certainly no exultation and no heady optimism, rather the reverse. We felt now that every man’s hand was against us and that we were little better off than escaping criminals.”

“We trekked entirely by night to begin with, as we had no civilian clothes,” Lang recorded in an official report of their journey toward the French coast. When rumours of a British landing proved false, the group acquired supplies and clothes but were soon recaptured. After being confined to a POW camp in occupied Belgium, Lang and three others made their escape on 14 July 1940.

Lang and Johnnie Buckingham crossed back into France and found farm work while being hidden by a French family. After a month in hiding, and with knowledge of two escaped British officers spreading in the community, they were next concealed in Lille by Red Cross worker Sally Siauve Evausy and her husband French medical officer Georges Evausy, a first war veteran. The two British escapees eager to get home, and Georges eager to join the Free French forces, travelled to Paris in hopes of finding an escape route. With the aid of several civilians, and through a circuitous route, the three crossed into unoccupied Vichy France by late October.

In Marseilles, Lang learned that the Vichy government interned many British escapees, who were technically considered to be on parole and free to move about within the boundaries of the town. After nearly a month, Lang managed to raise bribe money to stowaway on a boat bound for Syria along with a French Jewish businessman named Ben Slor. They evaded detection until arrival in Beirut where they went to the British Consulate. With Syria under Vichy control, the country was no safe haven for a British escapee or his Jewish friend. With assistance of people through the American consulate, the fugitive pair were driven to Lebanon and then made the long journey on foot across hills toward British Mandatory Palestine.

In Marseilles, Lang learned that the Vichy government interned many British escapees, who were technically considered to be on parole and free to move about within the boundaries of the town. After nearly a month, Lang managed to raise bribe money to stowaway on a boat bound for Syria along with a French Jewish businessman named Ben Slor. They evaded detection until arrival in Beirut where they went to the British Consulate. With Syria under Vichy control, the country was no safe haven for a British escapee or his Jewish friend. With assistance of people through the American consulate, the fugitive pair were driven to Lebanon and then made the long journey on foot across hills toward British Mandatory Palestine.

“The improbability,” Lang later wrote, “of two lounge-suited Europeans carrying suitcases visiting a remote Arab village at that time of night was obvious, but who were we to argue.” Throughout the trek they depended on an Arab driver and then further Arab guides. Even more improbably one of locals to aid their trek was an elderly man who had lived for a decade in Canada. They finally crossed into Palestine on 20 November 1940.

Reporting to a Somerset Yeomanry outpost near a Jewish settlement, Lang reported, “It was naturally extremely difficult for us to establish our identity, dressed as we were in our dirty suits and having no papers on us … Once we arrived in Jerusalem we were at last accepted for what we were.” Only a few years earlier, Lang had served there with the Camerons. In his book, Lang recounted the incredible end to his ordeal on seeing a Yeoman sentry:

With a shout of joy I rushed into the roadway and threw my arms round his neck!

His reaction was understandable. He looked at me in incredulous horror. “What the hell do you think you are doing?” he shouted. “And who the bloody hell are you anyway?”

With all the dignity I could muster I said, “I am a British Officer and I have just arrived from France and Syria.

“You may be the …. King of Siam for all I care!” he snorted. “Come with me while I wake the sergeant!”

The officer on duty turned out to be an old schoolmate, and although the British soldiers remained suspicious, “the atmosphere thawed a bit and we were given some strong tea and bully beef with bread. We were certainly back with the British Army!” On arrival in Jerusalem, his identity was finally confirmed by longtime friend Major Harry Cumming Bruce (who would command the 1st Battalion, Gordon Highlanders in Normandy during the 1944 campaign).

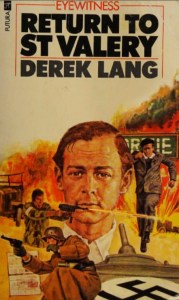

After a journey of five months and two escapes, Lang earned the Military Cross. He would narrate his remarkable experience in a 1974 book, Return to St Valéry: An Escape Through Wartime France:

The first few days of freedom were bliss. I had lived so long in discomfort that I had almost forgotten the little refinements of civilization—having one’s shoes cleaned, the morning papers, drinks before luncheon, and so on. To add to my euphoria was the warm feeling that in a few days I would get a posting home for some leave and that I would soon be reunited with my family.

His attitude changed when he learned that he was to be ordered to report to Middle East Headquarters in Cairo:

I nearly fell through the floor. It was not to be home after all but straight back into the war. My rosy picture of the hero’s return died a sudden death. The Adjutant misunderstood my woebegone expression. “Cheer up”, he said, “I don’t think they will give you a staff job. You will be with your regiment in the desert in no time.” His forecast was accurate.

(Return to St Valéry, 178).

Lang returned to duty, serving with the 2nd Battalion, Cameron Highlanders in East Africa in January 1941. In June, he was with the battalion in North Africa where he was nearly was captured again after being encircled at Halfaya Pass. This was followed by staff training, a posting to SOE directing agents in the Balkans, and instructional duties. By late 1942, Lang returned to the United Kingdom to be chief instructor at the school of Infantry based at Warminster.

At the end of July 1944, Lang returned to active duty in the field to take over the 5th Battalion, Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. Major C.A.H.M. Noble had been wounded days after Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Cairns had been put out of in action. “My joy knew no bounds and within twenty-four hours I was across the Channel,” Lang wrote of the appointment. “I took over the 5th Camerons while they were still in the invasion bridgehead. Shortly afterwards we broke out from Caen and started the victorious march of liberation through France.” During this time, Lang reunited with several of the French civilians who had aided his escape four years earlier.

He led the 5th Camerons throughout the rest of the campaign and earned the D.S.O. for an assault on 14 November. The regimental history offered a tribute to his long tenure as CO:

Derek Lang had commanded the Battalion for eight months of almost continuous action, no mean feat in itself, and had guided it safely and surely from Normandy to Germany. In action he achieved the confidence of all ranks, and the high and genuine regard in which he was held did not arise from his personality alone but also from his great courage and ability as a leader. Out of action, he concerned himself equally wholeheartedly with the welfare and social activities of all members of the Battalion. It was a sad moment when the Battalion said good-bye to him.

(Historical Records of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders 1932-1948, Part 2, Vol. 6, 151)

Lang relinquished command in May 1945 to set up the School of Infantry at Sennelager, Paderborn in occupied Germany. He served the British Army for thirty-five years and retired as general officer and commander-in-chief of Scottish Command in 1969.

Lang was knighted in 1967 and died in Kirknewton, Midlothian on 7 April 2001.